Social distancing, shuttered businesses, and working from home. All effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The measures in place here in Ottawa have brought to a light a different kind of issue - Ottawa has some serious design defects, and it's going to take a little elbow grease to fix them.

COVID-19 has caused massive disruption to life across the world. Locally, that disruption has presented itself as offices emptying for work-from-home policies, limited car traffic, limited public transit use, and limited trips outside the home.

You may have noticed other changes around you. Did you ever just walk around your neighbourhood before quarantine started? Did you do it everyday? Have you ever seen so many people walking, biking, and skating?

Even in the middle of summer, when kids weren’t in school and many people were on holiday, I don’t recall seeing so many people just wandering around outside. It’s a stunning change from the same time last year.

This will play out not just in the tech sector, but across almost every sector. Office space is expensive, and cutting down on it is almost a given as 1 – working from home is proven viable on a large scale, and 2 – economies contract in the wake of the virus shutting down businesses and commerce worldwide.

In cities worldwide, can we image what this could look like? Existing office space only half-full. New office construction projects suddenly shelved. Maybe there will even be an increase in demand for 2-bedroom condos/apartments or houses as workers look to create a true home-office.

At the same time, real-estate companies owning existing office space will start losing money as no new tenants fill the void. Cities will start losing a valuable stream of revenue. It may take years for these vacancies to fade.

On the transport side of things, with fewer people needing to commute every day to an office, roads will be more open than ever. Public transit will be emptier, and struggle even further to attract riders and break even. Perhaps former public transit users will switch to automobiles due to stigma around the spread of sickness, or due to the newly uncongested roads.

If communities are not equipped to handle more people working from home, then they may also see an increase in driving, as workers run errands during the day or grab food for lunch. While a city’s downtown core may be accessible on foot or bike, this will be a much more likely occurrence in suburban neighbourhoods, where the nearest business can be many kilometres away.

While in the long term we may see a return to “yesterday’s normal state”, we need to consider that some of the changes COVID is causing will become permanent. Further, on the long-term horizon are even greater disruptions to cities. One of the largest on my radar is the adoption of self-driving vehicles. Check out the keynote presentation from the NC DOT Transportation Summit in North Carolina.

Cities are in for waves of disruptions, and the status quo we had is possibly gone forever.

Here in Ottawa, life goes on, even in this altered state. That also means municipal governing committees are still at work. You may be aware that the planning committee is currently discussing the next official plan, which will set development land and priorities for the city until 2046. The expectation is that the city of Ottawa will grow by about 400,000 residents in that time-frame. Under a balanced scenario, the planners are looking to accommodate about half of those residents in new developments, and want to open up another 1,650 hectares of land for new housing. The rest of those residents would move to the city’s existing urban areas through intensification.

The expansion of the newly built light-rail continues, as the Orleans, Baseline, Moodie, and Riverside South/Airport spur expansions are now in various states of planning and construction. This $4.6B project, partially funded by the federal, provincial, and municipal governments, will add 24 new stations and 44 new kilometres of track.

Obviously, there are some important considerations we can relate to both of these developments. First, an expanding urban boundary means more far-flung suburbs, and before COVID would have meant more cars on the road. With the current state of affairs, it is possible that there will be a permanent reduction in cars headed downtown. There is also the possibility that cheaper office space will end up opening in these distant suburbs, thus changing commuting patterns and de-centralizing the city.

Second, our rapid-transit system will effectively serve the suburbs, and while it currently does a good job of bringing people downtown, it could just as easily serve as a connection between all areas of the city, if de-centralization is what occurs. Some projects, like the seemingly forgotten Baseline BRT could offer these important connections.

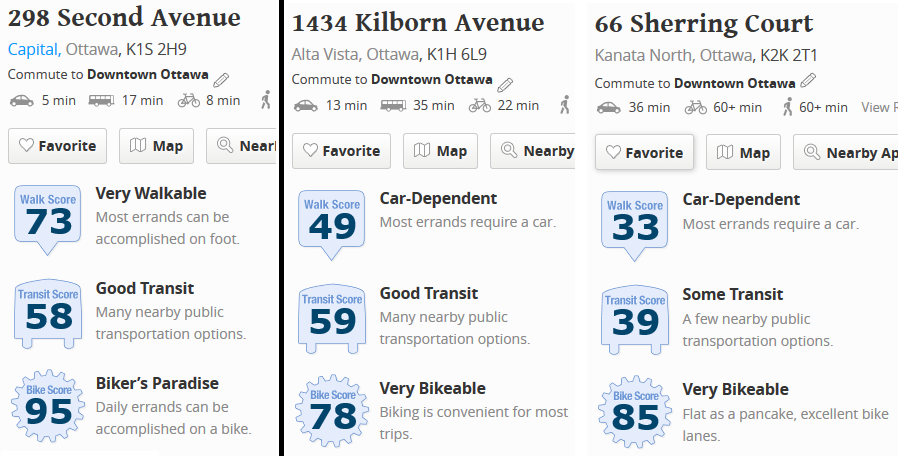

I still have some lingering questions about our future city. One is the current layout of our communities. Specifically, how accessible they are without a vehicle.

Think about it this way. In the middle of winter, how easy is it for you to get groceries, shop for necessities, shop for leisure, walk to school, or the gym, or your doctor, or your work, in your neighbourhood. For most people outside of very central areas, the answer will probably be one or none of the above.

This is a fundamental issue in our city’s design. It is a calculated flaw, as restrictive zoning separates residential areas from commercial areas, completely in many cases. Bylaws are also incredibly restrictive on home-based businesses. Reading the city’s bylaws is highly informative in this regard. Notably, parking can only be provided in the home’s driveway, only one sign is allowed, and only one employee from outside the home is permitted to work there at any one time.

There were already people who could not afford a vehicle forced to live in areas where walking and biking to destinations is difficult. With significant impact to jobs occurring now, that number may grow.

Walking is not only difficult due to distance. Unfriendly pedestrian infrastructure also plays a major role in reducing people’s ability to get around. Many streets are wide, but have just a skinny sidewalk on one side, or none at all. Major thoroughfares often have narrow sidewalks next to busy, high-speed roads. One of the most egregious examples of unfriendly pedestrian infrastructure I can think of is Walkley Road.

Would you want to walk anywhere on that?

Any solutions the city comes up with should take these people into account.

On the transit side of things, I can only imagine how COVID is going to impact people’s perception of transit, and subsequently, their use of it. Traveling in a metal tube like a bus or train, in close proximity to others, doesn’t feel like a safe choice right now. Once work places start to reopen, we will find out how this plays out. It may take years for ridership to rebound. It seems like an unfortunate time to be expanding the transit system, so hopefully public safety is very visible when the expanded train service opens.

I think COVID-19 has brought to light some of our city’s deepest problems. Our city was designed around the car, and it feels like the government still has that mindset. Many of our neighbourhoods are not walkable, and services are unreachable on foot.

A solution for these problems will take a long time to bear fruit, but now is absolutely the time to deploy it. I think a quick-win for the city would be to reduce the onerous restrictions on home-businesses, and to move towards a less restrictive zoning setup in general. Letting people access services in their own neighbourhood will not somehow destroy their quality of life. In fact, it can contribute to the healthy renewal of a community.

Hand-in-hand with this would be deploying something like complete streets across these communities. Infrastructure should support pedestrians, cyclists, transit and cars, in that order, rather than mostly just cars as it currently does.

Wider sidewalks even have an added benefit of allowing people to socially distance effectively, without needing to step into the road.

For the challenge of bringing ridership back to public transit, there is a much steeper hill to climb. The issues aren’t something that can be legislated away. We can’t afford to have people continuing to get sick, and unfortunately public transit is a potential place where that can easily occur.

The city will need to accept that ridership may be reduced for some time, until the crisis is fully passed. Upgrading the system will not necessarily lead to improved revenue. That said, maintaining at least current levels of service should be the goal. Users won’t ride now because of factors outside of the transit agency’s control, but they definitely won’t ride if service is permanently cut.

I’ll leave you with some food for thought. We need to look at the change forced upon us by this virus as an opportunity to build a better city.

With less people driving, and more people getting active outside, I can already see an incidental benefit – less commute related stress, and a generally healthier population. Reducing dependence on cars can help people lose weight, and achieve better long-term health outcomes. Not only are you less likely to be injured in a car accident, but it can also help reduce the risk of things like heart attack or stroke. This would lead to less burden on the health-care system, saving everybody money in the long-run!

Better neighbourhood design could also lead to a more affordable city as well. Currently, high demand in the city’s core means prices are very inflated there, relative to housing in the city’s suburbs. Improved neighbourhoods across the city could lead to broader demand across the city, reducing the pressure on central areas. This could, in turn, improve the potential for everyone in the city to be able to afford their preferred housing.

If the city is opening up vast new tracts of land for development, then let’s make sure those new neighbourhoods are developed in a people-friendly way, rather than the way we always seem to follow.

This ideal is also why we need a strong public transit network. Having a city stitched together by rapid transit will allow everyone to access needed services and jobs, without needing to spend money on car ownership and upkeep.

We can have a better designed city. If any of this resonates with you, reach out to your city councillor and start asking for it.